How My Native Son Was Caught in the Crossfire of Oklahoma’s War on Tribal Sovereignty

McGirt v. Oklahoma was a landmark case that significantly altered the legal landscape in Oklahoma. In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma shook the legal foundation of Eastern Oklahoma by affirming that much of the land promised to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in treaties remained sovereign tribal territory for purposes of criminal law.

Recently, the states response has revealed a more troubling reality. McGirt did not erase the deep-rooted government resistance to tribal sovereignty, or the pattern of constitutional violation committed under the surface. Oklahoma leaders, including Governor Kevin Stitt, argue that McGirt protects violent criminals while ignoring cases of falsified police reports, federal civil rights violations, and police intimidation.

The State cites Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta as the backbone of their argument. A non-Native man, charged with child neglect against a Native child on tribal land. Yet, the state of Oklahoma, and especially Gov. Kevin Stitt has used that decision to justify a broad reclamation of prosecutorial power.

"Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta, a non-Native, was convicted in Oklahoma state court of child neglect, and he was sentenced to 35 years. The victim, his stepdaughter, is Native American, and the crime was committed within the Cherokee Reservation."

Castro-Huerta challenged his conviction, arguing that under the Supreme Court’s 2020 decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which held that states cannot prosecute crimes committed on Native American lands without federal approval. Oklahoma argued that McGirt involved a Native defendant, whereas Castro-Huerta is non-Native, so McGirt does not bar his prosecution by the state.

So, how did Oklahoma officials (including Gov. Kevin Stitt and AG Genter Drummond) and several Oklahoma DA’s frame this as a broad restoration of state jurisdiction? They applied the logic of Castro-Huerta to assert state jurisdiction over Native defendants, which the ruling explicitly does not allow and framed it in the media as justice for violent criminals.

The U.S. Department of Justice filed preliminary injunctions against 2 DA’s on Monday, Dec. 23, 2024. Carol Iski (District Attorney, District 24 for Okmulgee, Okfuskee, Creek, and McIntosh Counties) and Matt Ballard: one of the most vocal critics of McGirt.

Ballard’s office has repeatedly been documented misusing tribal status to delay or deny due process. Charging Native defendants in state court with full knowledge that they lacked jurisdiction. His public statements focus on “violent criminals walking free,” but his filings and case records show routine prosecution of non-violent offenses. He has been accused of influencing judges to ignore tribal status during arraignment and bail hearings and letting prosecutions proceed before tribal jurisdiction could be asserted.

Carol Iski has been named in two DOJ lawsuits for alleged misconduct involving Native American defendants and is notoriously aggressive in asserting state jurisdiction, including over Native people and on tribal lands, even when clearly preempted by McGirt.

The DOJ’s lawsuit asserts that Carol Iski has prosecuted “at least four” Native defendants under state jurisdiction for acts within Indian Country, even though McGirt clearly prohibits that authority, two of which were non-violent: Oklahoma v. Joshua Medlock for possession of contraband by inmate, Oklahoma v. Joey Wiedel for contraband.

Similarly, in the lawsuit against DA Matt Ballard, he is accused of prosecuting three Native defendants in state court for offenses that allegedly occurred within tribal jurisdiction. While Matt Ballard claims to be focused on prosecuting violent offenders, the DOJ complaint shows that many of the cases his office pursued, including Oklahoma v. Eric Ashley for drug crimes and child neglect, still fell under tribal authority.

The state’s refusal to acknowledge these boundaries is what created the very backlog of cases they blame on McGirt. Violent offenders walked free because the state wasted months filing charges in courts that had no authority to hear them.

My Son’s Story: When the System Targets a Child

The abuses of jurisdiction and constitutional rights described in the DOJ’s lawsuits aren’t a distant problem for violent criminals. I’ve experienced them firsthand.

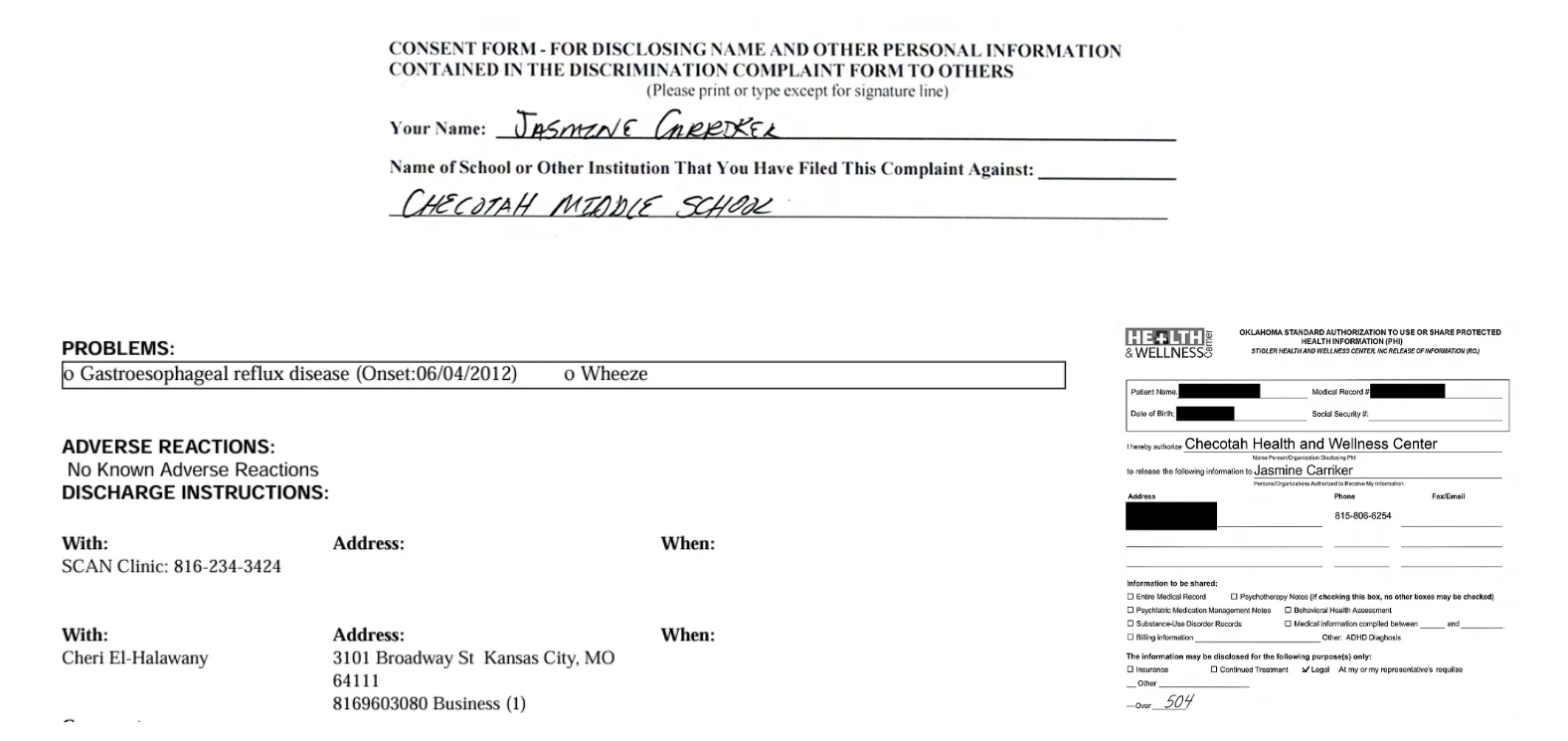

At the time, I was still employed as the librarian in the Checotah Public School district and worked closely with the IT department to fix minor software and hardware issues and assess damage to Chromebooks. I was in a disagreement about my son’s lack of a 504 plan and bodily autonomy with principal Shawndy Young, of Checotah Middle School on April 22nd, 2025.

Jasmine Carriker, Librarian at Checotah High School

My son had slipped out of the classroom to use the bathroom after being denied by a substitute, despite it being an emergency. It was the first time he had ever done so. When he returned, he apologized and said, “I do think it’s a human right to go to the bathroom in an emergency”. Mrs. Young called me at work and demanded additional medical documentation to his already documented illnesses when I said I “didn’t disagree with his statement”, before allowing a 504 plan to be initiated. She claimed that, even though he had remained calm, his statement was “disrespectful to authority”.

I tried to advocate for him, offering medical paperwork, although he was already diagnosed with GERD and ADHD: the latter condition for which the school was dispensing his medication. I had a conversation with Superintendent Monte Madewell, where we seemed to reach an agreement. Days later, at work, I was pulled into the office and told I was “making mountains out of molehills”. Fearful of retaliation, I sent my resignation that day and filed a complaint with the Department of Education — Office of Civil Rights.

On May 13th, my son, a 13-year old member of Cherokee Nation, was accused of damaging a school issued laptop in McIntosh County. I had dropped off the laptop that morning at the school. I was the last person in possession of the laptop and fearful of retaliation, I made a voice recording while I was walking in the building at 9:24am on May 13th, 2025. A voice saying, “Just sit it there and I’ll give it to him when he gets back” can be heard on the recording.

Voice recording of Jasmine Carriker dropping off Chromebook at Checotah Middle School

Forty minutes after I dropped off the Chromebook, Checotah police officer and ex-coworker, Ronald Goad, called me and asked that my partner and I come speak with him at the station and would not disclose the charge. I immediately retained an attorney, and from that point forward communication was directed through legal counsel. On May 22nd, I questioned him on the charges.

While at the police station, my partner and I overheard a conversation between several officers discussing a recent DUI traffic stop in connection to the Oklahoma v. McGirt decision. During the conversation, one of the officers made a racially charged comment suggesting that “Natives aren’t really Native” and that “there were people here before them.” The remark reflects a broader culture of hostility or misunderstanding regarding tribal sovereignty within the department.

Officer Ronald Goad responding to allegations on May 22nd, 2025

When I informed juvenile coordinator Sandi Guess, of the McIntosh County, her response was not professional — it was a warning. She told me that if I didn’t “cooperate,” they would refer the case to the District Attorney because, in her words, she “knows her.” Sandi Guess and DA Carol Iski proceeded to set a court date without informing me of the charge.

Juvenile Intake Coordinator, Sandi Guess, admits she knew we were Native, has the police report, and fails to disclose charges as I question her on the lack of information.

But the intimidation didn’t end there.

Officer Ronald Goad, the same Checotah police officer employed by Checotah High School, who had called me without disclosing the charges, also attempted to intimidate me publicly. At the high school graduation ceremony, he stood less than an inch from my me, refusing to move, until I raised my camera to my neck and hit record. His message was clear: I was being watched.

He didn’t just intimidate me. He has intimidated a former coworker of mine, in a similarly aggressive manner. She, along with others in the district, had privately voiced serious concerns about Principal Shawndy Young, specifically regarding the mistreatment of students with disabilities. But fear of retaliation kept them from speaking out.

Despite the fact that my son is a Native minor and the alleged incident occurred within the boundaries of Indian Country, the State of Oklahoma filed charges in McIntosh County Court without ever notifying or consulting the Cherokee Nation or Muskogee (Creek) Nation. And for asserting my right to legal counsel, I was labeled “uncooperative.”

Exterior Front View

Exterior Side View from Parking Lot

Arson. There was no fire, no police report from the school on that day, no disciplinary action, no evacuation, no call to the fire department. The laptop remained in our possession until I personally returned it, undamaged, on May 13th after emailing the school to ask if they needed it back when my son forgot it at home.

When arson couldn’t be prosecuted, it was “malicious destruction of property”. However, the school IT department found no damage to the laptop except for an unreliable USB port, a common issue on cheap Chromebooks. Still in a court with no lawful jurisdiction over Native children on tribal land. My son was placed on house arrest and monitored like a violent offender. He is being threatened with a year in juvenile detention for a “fire” that started no fire and a “damaged” Chromebook that wasn’t damaged.

I won’t stay quiet. What happened to my son is part of a larger pattern and one that the DOJ is finally beginning to investigate. If Oklahoma wants to talk about law and order, it should start by following the law. Until then, the real threat to public safety isn’t McGirt, it’s our corrupt justice system.

If you’re a parent, educator, journalist, or civil rights advocate with a similar story or concern, I welcome you to reach out. You can contact me via email at jasminecarriker@gmail.com